“The ear of the writer is her most precious attribute. When well developed, this ear brings analytic precision, compositional fluency, and technical skills that are necessary to create and craft writing.” - Dominic Wyse, How Literacy Works

Developing an ear for writing doesn’t appear to be in elementary school success criteria and yet, possibly one of the most established researchers in literacy, Professor Wyse from University College London, sees this as the main area for development in our future writers.

"Every writer I know has trouble writing" - Joseph Heller

For a teacher, distinguishing between developing an ear for writing as Wyse describes, and letting students know that writing is difficult and a craft as Heller suggests, provides a real challenge, especially when the curriculum asks for "greater depth" alongside "fronted adverbials". This is further complicated when looking at children with "spiky" profiles. Those who shine in some areas dull as soon as pen reaches paper; the sparkle is lost and the assessment process may mask their true academic potential. So how can we attempt to close the attainment gap for these children?

There are many children who can achieve more in their writing if different strategies are used. It can be frustrating as a teacher, a parent, or for the student when there is a discrepancy between what they say and what they write.

Why is this? And what can you do about it?

Short-term memory:

"Hold that thought" is not something children with poor short-term memories can do. They say (or often blurt out) something brilliant and then it has faded away either naturally or because someone or something has disrupted the thought process. It can even happen mid-sentence. Have you met those children who begin telling you something and then hesitate and say, "I’ve forgotten what I wanted to say now"? Or those children so desperate to tell you something that they put their hands in the air as if their lives depended on it, but when you get to them, they’ve forgotten the answer? This type of behavior may mean a child has a short-term memory difficulty.

Strategies to trial:

- Use talking tins or dictation software such as voice memo on the iPad - the student talks into it and then can listen back over and over again until it’s written.

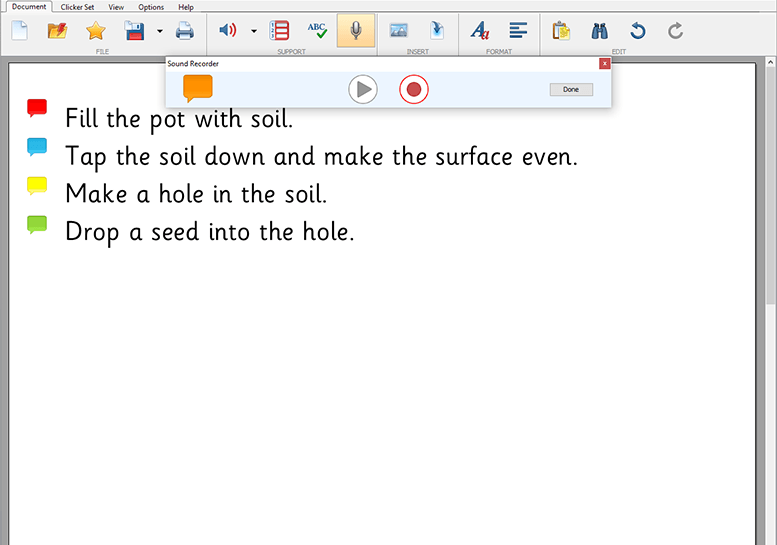

- Clicker 7 also has a Voice Note function which is excellent to use in their word processing software - not only can learners press to hear what they want to say, in conjunction with predictive text and the word grids, they can be freed up of all their literacy difficulties.

- Try visual note taking or drawing images to use as memory prompts - it won’t solve the full sentence but could generate enough information to trigger memory and build writing content.

- Paired writing can help get ideas down or collaborative writing is a fantastic way for students to achieve and feel proud of their work. In addition, they are learning through modeling.

- Speech-to-text software can allow a student to speak their writing, which may alleviate both memory and spelling barriers.

Retrieval:

An inability to generate a lot of words quickly. Ask a group to write as many words as they can which mean the same as "cold" or write as many animals as they can with four legs. You will find some children (and adults) cannot generate words quickly despite knowing them, whereas others will barely stop as vocabulary comes streaming out of their long-term memory. For the former child, this may not mean they have a limited vocabulary, more so that it is hard to retrieve words. The same can happen when writing despite, when in discussion (with lots of memory triggers), they appear to speak fluently and with a wide vocabulary.

Strategies to trial:

- Lots of discussion beforehand. Pie Corbett’s Talk for Writing is an excellent way into writing through language.

- Pre-writing activities help generate rich vocabulary. This can include drama, talking partners, and video prompts.

- Visual prompts or triggers.

- Word walls.

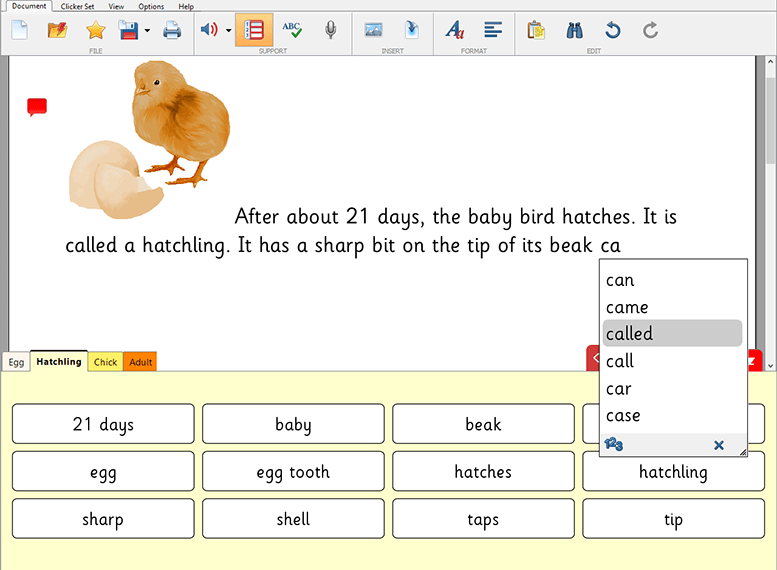

- Using word banks in Clicker 7 to give children instant access to more adventurous or topic-specific vocabulary. These can be made by the teacher or created collaboratively "on the fly" as a pre-writing activity.

Sequencing:

Many learners struggle with sequencing their thoughts and getting these down on paper in a coherent way. This is linked to executive function which in part is "in charge" of organization. Students who struggle with this may have all the information but struggle to put it in order or into a linear format. I liken it to an index card holder. If you want all the cards beginning with G, you can easily find them by searching alphabetically. A student who struggles with sequencing however, may have all the information in hand but it has been thrown all over the floor, making it much harder to find.

Strategies to trial:

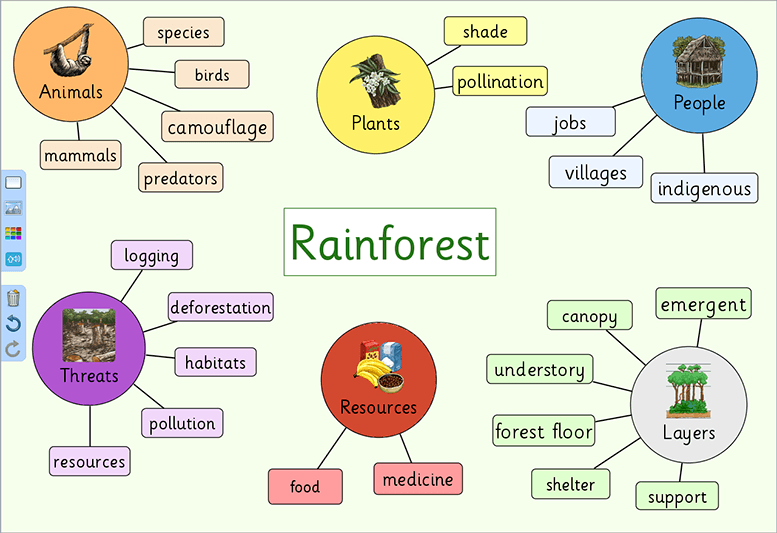

- Concept mapping such as mind maps and spider diagrams. This allows for a "brain dump" of ideas before turning these pieces of information into a linear format. There are software versions of this skill (for example Clicker or DocsPlus) which will, with a click of a button, switch between concept map and linear. As a teacher, these can be used as writing frames if printed out, win-win! If you want to just use a simple spider diagram with a few words or possibly images then an iPad app called Popplet is brilliant and as an added bonus, it is easy to print off as evidence.

- Storyboards - obviously to sequence stories these are useful, especially if you use a story arc to begin the planning process. Story boards are also useful however, to sequence any ideas for writing. A simple sheet of paper with 6 boxes, preferably with room for lines at the bottom is ideal. There are also apps and software to make books and I personally love the ease and utility of Clicker’s iPad version, Clicker Books.

- Structure strips were the brainchild of elementary school teacher Stephen Lockyer, and are inspired. I believe they are a true scaffold and offer the guidance children may require to know what to write, in the right place and at the right time.

Speed of processing:

Children who have slower processing speed are often as able to achieve as their peers but they need more time. What doesn’t a teacher have? Time. I know, I know. But to close the attainment gap in writing for these children, reasonable adjustments will be required. One student once told me, "I wouldn’t mind Miss, but I only bent down to pick up a pen and we were onto the next thing!" We’ve all been there, haven’t we?

Strategies to trial:

- If you use predictive text and word banks in Clicker 7, this can speed up the process tremendously and allows the student to write quickly and fluently.

- Less is more. This stands to reason - if you can’t make more time, then ask the child to do less. Perhaps they can continue with a task when others have moved on (if it doesn’t mean they’ll miss curriculum content) or use bullet points to structure but with one or two well written pieces to show depth. Quality not quantity.

- "Slow writing" first came to my attention when The Learning Spy began writing about them. I have used them regularly and find they are great for developing "the ear" for writing and allowing children to learn how to craft sentences.

Phonological awareness:

The ability to reflect upon and manipulate the sound structure of words. In writing, this difficulty will show in spelling. But when a child struggles to spell it can impede their writing significantly, affecting fluency, vocabulary, and confidence. Some children will only write words they know they can spell and this means much writing will not reflect their verbal ability. With all the effort of trying to spell and write, a child’s working memory may be taken up with concentrating on this rather than the content of their writing. Freeing up the cognitive load could really help with the fluency of their writing, liberating them to be creative and relaxed. For assessment purposes, under this climate, a teacher can really see their potential.

Strategies to trial:

- Allow spellchecker on the laptop to free up working memory on writing.

- Use word grids and predictive text in Clicker 7.

- Try speech recognition software or a scribe.

A word about groupings and challenge...

"Novice writers, including those learning in schools, encounter teachers as gatekeepers of topics, forms, means and processes. But those teachers are often constrained by systems, including the accountability that tests and examinations required by governments engender." - Wyse, How Writing Works

Included in this mix are learners with additional needs and spiky profiles, making it tremendously challenging for a teacher to maximize writing potential for all in their class.

Often children with the difficulties stated above can end up on the "bottom" table, or tasks set may be fixed at a very low bar. This counts for all children, really. Do you know your children’s individual skills and potential? Might they surprise you if you let them choose tasks without limits? With a variety of strategies and high expectations, children can often achieve fantastic things.

Furthermore, as this article encourages, a child with a specific difficulty such as dyslexia may have literacy as a barrier, but it does not mean they are low ability. Be vigilant and find strategies to enable them. Discrete phonic lessons are needed but not at the expense of a broad and balanced curriculum, and challenge at the same level as their peers. As Mary Myatt writes, set high challenge but with low threat. Catch children succeeding by removing barriers rather than creating a system that sets them up to fail. In the current climate, I know that can be difficult, but with strategies like those suggested above, these children can show what they are truly capable of achieving.

Jules Daulby is a public speaker, trainer, and writer on inclusion, literacy, and positive behavior strategies in Special Education. She is also co-founder and a national leader of #WomenEd, a grassroots organization supporting existing and aspiring women leaders. Formerly director of education for a literacy charity, literacy lead for a pyramid of 16 schools, and a teacher. She has over 20 years' experience in mainstream state education in elementary, secondary, further education, and parent partnership. Jules has particular expertise in inclusive teaching and learning strategies and specific learning difficulties such as dyslexia/ADHD. She believes assistive technology is key for these students to achieve more. An advocate for comprehensive education and campaigner for the reduction in exclusion and segregation of vulnerable children.